For the past two years, Bryan Cranston (Hal) has won the Emmy award for Best Lead Actor, for his role as Walter White in Breaking Bad.

Now almost finishing its third season, Breaking Bad and Bryan seem likely to be nominated again, with network AMC producing their campaign DVDs, including six consecutive episodes of the show and The Hollywood Reporter publishing an ‘Emmy Roundtable’ which includes Bryan.

Competition will be tough, however, with Bryan and Breaking Bad up against other ‘tough guy’ characters.

Bryan Cranston, a two-time Emmy winner for playing meth-dealing high school teacher Walter White on AMC’s “Breaking Bad”: “This is the character of my career. He has such broad parameters that I can go from being sensitive and concerned to heinous and evil in the same episode. You never know what to expect when you get the script.”

That’s a big change, Cranston says, from when he began his acting career playing cookie-cutter villains on police dramas and action-adventure shows. Cranston met his wife playing such a part on an episode of “Airwolf” 23 years ago.

“I was the ‘bad of the week’ and she was the ‘victim of the week,’ and that’s how men’s and women’s roles were written back then,” Cranston says. “Fortunately that’s changed, and we’re seeing a more equal-opportunity bad guy come forth.”

Bryan will also be up against plenty of previous nominees as well, including big names such as House‘s Hugh Laurie and Michael Emerson from Lost.

Bryan also speaks of his transition from Malcolm to more serious roles in this article from The Hollywood Reporter:

“You can become a victim of your own success,” adds Bryan Cranston, who has won two Emmys for his serious “Breaking Bad” role but who spent six Emmy-free years on the comedy “Malcolm in the Middle.” When that show ended, he recalls he was offered a lot of “derivative, silly dad” roles.

“It’s up to the actor to get themselves out by carefully picking and choosing,” he says. “The only real power we have as actors is to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and identify well-written material. I never want to be embarrassed by what I’m doing.”

For each of his major roles, Cranston recalls having someone go to bat for him; first it was “Malcolm” executive producer Linwood Boomer, when word came down that executives might want to recast Cranston’s Hal role after the pilot. With “Breaking,” Cranston says, “I heard through the grapevine that the studio questioned whether the goofy dad from ‘Malcolm’ was the right choice. I was confident that the transition could be made, and Vince (Gilligan, “Breaking’s” creator) spoke for me. That’s a big leap of faith.”

The Emmy Nominations will be revealed on Thursday, July 8th at 5:40am Pacific Time. The event will be live from the Leonard H. Goldenson Theatre on the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences campus in North Hollywood and will apparently also be streamed live on emmys.tv.

“Mad Men” not only made Emmy history by becoming the first basic-cable TV show to win a best-series award in 2008, but it also repeated the triumph in 2009. For the last two years, AMC also pulled off surprising consecutive wins in the race for best lead actor by Bryan Cranston (“Breaking Bad“).

Next: Can AMC pull off the victories for a third year in a row?

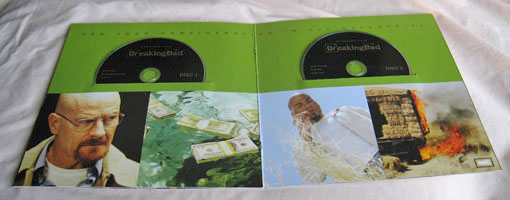

A lot depends on what Emmy voters think of the campaign DVDs shipped to 14,000 members of the TV academy. Though some networks are skimpy and merely send two or three sample episodes, AMC sends six. It’s curious that AMC chose six consecutive episodes of “Breaking Bad,” but it broke up the “Mad Men” selections. Below is the rundown.

Also included in the DVD box: “The Prisoner,” AMC’s miniseries update of the bizarre 1960s TV series about a government agent trapped on a mysterious island. Stars James Caviezel as the prisoner and Ian McKellen as his tormentor

Compare this year’s Emmy campaign box with the one AMC shipped last year. Underneath the photos below are links to DVD campaign boxes sent by other networks.

“MAD MEN”

Episode 303 – “My Own Kentucky Home”

306 – “Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency”

307 – “Seven Twenty Three”

311 – “The Gypsy and the Hobo”

312 – “The Grown-Ups”

313 – “Shut the Door, Have a Seat”“BREAKING BAD”

Episode 301 – “No Mas”

302 – “Caballo Sin Nombre”

303 – “I.F.T.”

304 – “Green Light”

305 – “Mars”

306 – “Sunset”

“Who canceled that got me here?” Ray Romano joked as the first of The Hollywood Reporter’s Emmy Roundtable series began. Humor dominated the hourlong discussion in a penthouse at the Chateau Marmont, during which the drama panel poked fun at their wives, declared themselves narcissistic and told a major TV critic to “suck it.”

The Hollywood Reporter: When you guys watch your performances, what do you criticize most?

Matthew Fox: I don’t (watch). Never. I’m a fan of the show and I watched early on because I wanted to see how it was put together. But I don’t find any benefit in seeing what I’m doing.

THR: How about the others? Do you watch your shows?

Matt Bomer: Sometimes. You want to see the character come to life in an authentic way and hope you’re not mugging or being inorganic.

Alexander Skarsgard: I watch it and I’m blown away by my own performance! (Laughs.) No, every single scene, I’m like, “Oh man, way too big. That look is so redundant. Again with that flat delivery?” I really don’t enjoy it.

THR: Yet you keep coming back.

Skarsgard: I do. I’m like a drug to myself. (Laughs.) I did movies in Sweden before I came over here, and I would never watch dailies because I didn’t want to see myself in the character. But that obviously had to change (on a series) because I couldn’t wait seven years until the show’s over to go back and watch it. I still don’t watch the monitors; but when the season airs, I do watch it.

Jon Hamm: We don’t have playback on our show, but watching playback is a whole different experience because you’re right there and you’re like, “Ah, I can’t watch it. I wanted to do something else, it’s not coming through.” Watching a complete version of the show, you’re far enough away that you can feel separated enough to sit and enjoy it.

THR: Do you approach a dramatic role differently than a comedic one?

Bryan Cranston: You have to know the tone of your show. This show (“Breaking Bad”), for instance, is very dark, so the things I look for are the subtle opportunities to lighten it up a little bit. Every good drama has a nice sprinkling of levity to it, and every good comedy has its sincere moments to surprise the audience. What I don’t like is whenever the lay person in Nebraska can sense it — set-up, set-up, here comes the punchline. If the audience can sense it and is way ahead of you, you’ve lost them.

Ray Romano: The harder part on this show (“Men of a Certain Age”) is doing the comedy because it has to all come from a real place, (whereas) in a sitcom you can stretch it and get away with it a little bit. The difficult part is doing the comedy on the drama, believe it or not, because I feel the dramatic parts are just as real they can be.

Hamm: As depressing and sad and slow and boring (laughs) as our show can be, there are some really funny moments … that are usually given to (John) Slattery. (Laughs.) It’s important because that’s life.

THR: Do reviews hurt?

Hamm: Yeah, if they suck. If someone says you stink at your job, that doesn’t feel great. I can viscerally remember Tom Shales’ review of the first season of “Mad Men,” which said this would have been a good show if someone good had been the lead. And I was like, “Hmm!” (Laughs.)

Skarsgard: Who’s laughing now?

Bomer: Suck it, Tom Shales!

Skarsgard: I stay away from all that. It’s not just the bad stuff; I feel like the positive stuff might make my ego explode.

Cranston: When I first started 31 years ago, I took any job I could get and I was glad because I had rent to pay. But you would never put it on your resume if you were embarrassed about it. Now you can’t do that. In a way, it kind of keeps you honest. It’s going to be on IMDb before we start.

Romano: The sick part is, I don’t really believe the good (reviews).

Skarsgard: You believe the bad ones?

Romano: Yeah, the bad ones really get to me. If my father had hugged me once, I would have been an accountant right now. (Laughs.)

THR: Do you ever get frustrated by how your performances are edited?

Fox: Hell yeah.

Romano: That’s why you’ve got to create your own show!

Skarsgard: Do you guys shoot a lot of scenes that don’t end up on the show?

Fox: Writers intentionally write their scripts at 58 pages when they know they have to get the whole show down to 43 minutes; they want the control in the post process. That’s OK, but it does make it tough to play a character and be really specific about the moment, knowing that all the air is going to get taken out of it.

Bomer: The opposite can be true, too, where the air needed to be sucked out of it.

THR: Do you adjust your performance, knowing that might happen?

Cranston: No, you can’t second-guess what’s going to be cut, so you just have to hope that you go from A to C and they keep B. It’s when they cut out B, it’s a little jarring to watch.

Hamm: But the audience doesn’t generally know that B ever existed.

Fox: That’s always really amazing to me.

Hamm: There are always so many steps from shooting a scene to the finished product that goes on the air. You don’t know that they’re going to play music under something or how they’re going to tweak the levels and the light and the colors.

Romano: We can build a moment where a moment wasn’t there.

Hamm: Editing is an unbelievably manipulative tool.

Romano: You can write a different scene with editing.

THR: Bryan, what’s the biggest challenge you’ve found in directing yourself?

Cranston: I always start with a compliment about me! I respond well to that. I sleep with myself, too. (Laughs.) The hardest thing about directing is you’re also in it. I directed nine episodes of “Malcolm in the Middle” and I was in every one; and then this show, I’ve directed two so far. Hardest thing is to be able to know what other characters are doing, when your character is in the scene. There’s not a real way of definitively knowing, so I just print everything that I’m in and look at it in the dailies. It’s really difficult and I feel like there is a part that does suffer. For instance, I directed the first episode of the last two seasons. I did that because we weren’t in production yet and I needed the time. I would work all day, 12-13 hours, and I’d come home on my computer and write my notes and send my notes via e-mail to my editor and he would recut it and send it back two days later. You miss a lot if you’re not in the room with the editor and feeling the sensibility of it, so it’s a little frustrating. I think I may not direct again on the show.

THR: What’s the hardest thing about the acting side of the job?

Hamm: It is a big time commitment — especially on a network show — and you’re on an island, for some of us. It’s hard to be fully engrossed in it for so long. Family, other commitments — you’re so focused on one thing that everything else gets pushed behind you. And a lot of things tend to back up at the end of a run.

Fox: The publicity requirements: People don’t see how much time goes into that. Early on, when we were trying to launch a show, the publicity demands were just enormous.

THR: Did everyone in the cast bring their families to Hawaii for “Lost”?

Fox: Everyone with kids, yeah. As soon as the show took off and we felt it would be on for a while, everyone with kids moved them over and got them into schools. My wife and I have a rule where it’s never more than three weeks. No matter what I’m doing, we’ll pull the kids out of school if we have to because it’s never more than three weeks that I’m away from them.

Cranston: I have the same rule with your wife — never more than three weeks. (Laughs.) Just to keep it fresh.

Romano: I’ve been married 22 years, so with mine it’s the opposite: She wants me away for three weeks!

Bomer: “Get another show, dammit!”

Skarsgard: The hardest thing is the lack of control working on a television show. When you do a play or a movie, you have everything in front of you and I have my process, I know the arc, I know what’s going to happen and how I want to play the scenes. Suddenly you’re on a show where — we’re shooting Episode 9 right now and I haven’t read Episode 11 yet. I have no idea what’s going to happen.

Cranston: Episode 11? Sometimes it’s last-minute and the scripts don’t come in and we’re shooting the next day and we get it that night.

Hamm: That’s the same with us. We get the script at table readings, which is the day before (shooting).

Bomer: That’s nice, to get a table read. We get the pages day-of at times. The speed of this medium is so fast. We shoot an episode in seven days and a lot of times it’s 10-page days, so you’re just plowing through material so fast that you’ll do it in two or three takes and you have to let it go. A lot of times, that’s right when I’m getting comfortable.

Cranston: The work you do on the ride home is always the best.

Skarsgard: You wish they had a camera in the car, right?

THR: How often do you ask where your character is going?

Cranston: I don’t want to know. I’ve kind of gotten used to that, where I pick up the script and I’m excited to read it, almost like our fans are excited to see the next episode. So I play it that way. We do get showrunner-approved outlines about a week and a half before we start shooting, so at least you know in broad strokes where it’s going.

Hamm: You have to have a lot of trust in the people that are running the show. I’m the same way as Bryan: I don’t really want to know, I don’t want to play the end of the arc. I get very excited (to) read the next story. It’s fun to be surprised.

Fox: I do think not knowing –and, trust me, I’m on a show where we didn’t know … my background is in television. And in television you get involved in a premise, a concept and a character. Then you end up in a long run-on sentence. In a more contained medium, in a two-hour script, you do get to take more chances. You can reach for more when you’re looking at the entire arc of the character, how it exists in the context of the story. Series television, when you are in that situation where you don’t know where the characters are going, may subconsciously make you reach for less because you’re just going to have the rug pulled out from you down the road.

Bomer: I have a dialogue with the creator (Jeff Eastin) at the beginning: What’s the super-objective? What’s really motivating everything so I can take it one step at a time?

Romano: I just write whatever I can play. If I can’t play it, then I gotta change it.

THR: What’s the best way to resolve a dispute with a showrunner?

Cranston: Yeah, how do you do that, Ray? (Laughs.)

Romano: I have my guy, my partner (Mike Royce). We see things differently. But this is why I picked my guy, because I knew our sensibilities are the same — and if they’re not, we can talk about it. I am more easily talked out of things than he is, but only if I see his point. I never compromise. If I believe it, then I’ll go with it.

THR: Jon, do you ever say, “You know, I don’t think Don Draper would say this”?

Hamm: No. I don’t. It’s not because I don’t want to bring it up; it’s just that (creator Matthew Weiner) is very good at his job and —

Romano: You’ve never questioned any line?

Hamm: The only question I ever have is: “Where are we going with this?” And the answer always comes back, “Trust me, trust me.” It’s borne out. It’s not like I’ve been burned.

Skarsgard: Alan Ball and all our writers are very open to ideas. The other day, there was a scene and I had some suggestions, so I e-mailed the writer and he came back to me and we worked it out together. I do believe it’s important for the showrunner and the writers to invite the actors’ (involvement). If I don’t feel like I’m contributing, if I feel like I’m being shut down all the time, I’m not going to be able to do a very good job. At least convince me. Don’t just say, “It’s on the paper, do it.”

Romano: When I was on “Raymond,” I would argue with the showrunner, Phil Rosenthal. I would say, “It’s a sitcom, but I need to feel like (my character) would say that, and he would never say that.” And his argument would be, “That’s why you do it –because he would never say it that way!” I can’t argue, if the reason I would do it is because he wouldn’t. (Laughs.)

Fox: I’ve had experiences before with writers who were not open to the notion of me even changing a word, but my experience on “Lost” has not been that way at all. (Co-showrunner) Damon (Lindelof), I have an incredibly good relationship with him. We talk about Jack a lot and he’s always giving me the freedom to make it more fluid as long as the gist of what the scene was meant to accomplish was getting done.

THR: How much did the “Lost” writers prep the cast on the mythology of their characters?

Fox: They kept most everybody very much in the dark. They were very smart about only giving out pieces of information that they thought would influence the performance in the direction it needed to go. Damon gave me things that were going to happen and the directions in which the show was going to go for Jack, and I didn’t really know why he was giving me that at the time. Then six months later, I realized it was going to somehow color the entire way I was attacking the role.

Cranston: There really is a symbiotic relationship between actor and showrunner. Like Jon said, there’s a trust exercise that goes on.

THR: Is there a personality trait that all actors

share?Romano: We hate ourselves and love ourselves.

THR: You think actors share that trait?

Romano: Well, comedians. I mean no offense, but we’re really the most screwed up people around. In a good way. We’re narcissistic, but we also hate ourselves.

Fox: All human beings hate themselves.

Romano: I read an article where Dustin Hoffman asked Laurence Olivier, “Why do we do this?” And his answer was, “Look at me! Look at me! Look at me!”

Hamm: And then he farted. (Laughs.)

Source: Los Angeles Times, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety